Director Gurinder Chadha received a lot of flak for her film Viceroy’s House that is nothing but a loving tribute to the British colonialists. The film diverts the blame for Partition, to everybody but the British. In this version, the British were nothing but loving benefactors who loved the land and the country, and the Muslims and Hindus of India were merely squabbling kids who didn’t know what’s best for them.

The film opens with the arrival of a new Viceroy of India — Lord Mountbatten — to Delhi’s Viceroy House (now the Rashtrapati Bhavan). Mountbatten (played by Hugh Bonneville) and Edwina (Gillian Anderson ) are portrayed as well-meaning, good White people, who want to give India its freedom and stop the violence. Never mind, Lord Curzon’s earlier Partition of Bengal and the communal riots in Bombay, Punjab that took a huge toll on the communal harmony of the country.

Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Gandhi, and the others are fighting for their own version of what Independence will mean. For Jinnah, it is a separate Pakistan with Muslim majority population, for Nehru and Gandhi, it is an undivided India. Of course, there is a minor love story framed within a larger political context.

The Partition tore people, families, communities, and cities apart. Even today, Amritsar talks of its twin city — Lahore, and the almost-umblical cord like ties between the two.

While Chadha’s film might not be the best example of a film that captures the pain and pathos of Partition, a quick Google search will throw up around 20 films on the landmark historical event. After all, when historical and legal records fail to cover the pain, trauma and death, it is the various art forms that give voice to what Benjamin Walter had termed as the ‘expressionless.’

Nemai Ghosh’s Chinnamul is said to be the first film made on the subject, but we have Ritwik Ghatak’s Megha Dhake Tara, Deepa Mehta’s 1947 Earth, Chandar Prakash Dwivedi’s Pinjar, Kamal Haasan’s Hey Ram, and the 2017 Begum Jaan. Given that Hindi cinema, and therefore the larger Indian culture is influenced heavily by Punjabi families, we have seen and heard some of these stories, however, the equally bloody breakup of Bengal hasn’t been told much. We see it in Kamal Haasan’s Hey Ram and we see the aftermath of the Partition of Bengal in Megha Dhaka Tara, and the other two Ghatak films in the trilogy.

1947 Earth based on Bapsi Sidhwa’s Cracking India (Ice Candy Man in India) tells the story of Partition through the eyes of young Lenny Sethna. After witnessing some of the horrors of Partition where Hindu-Muslims, once friends, have turned against each other, Lenny comes home and tears apart her dolls. The scene is brought to life with these words from Sidhwa’s book:

“Adi and I pull the doll’s legs… until making a wrenching sound, it suddenly splits… The cloth skin is ripped right up to its armpits spilling chunks of grayish cotton and coiled brown coir and the innards… I examine the doll’s spilled insides and, holding them in my hands, collapse on the bed sobbing.”

In Hey Ram, Saket Ram, the protagonist (who perhaps is also the antagonist of his own life in many ways) of the story first encounters the idea of Partition in Punjab. Where the archaeologist Sir Mortimer-Wheeler announces to Saket and his friend that the dig will not continue. Saket, a Tamil man married to a Bengali woman, returns to Calcutta even as communal riots are breaking out. Over and over again, we see families being massacred, women raped, and killed, both Hindus and Muslims enacting their patriarchal hold over the women of the other side.

Both Hey Ram and the earlier, masterpiece-classic Megha Dhaka Tara are also about the deep personal tragedies wrought by Partition. Saket Ram is haunted by the death of his first wife Aparna, the violence he causes as revenge for her death – in particular the young girl whose father he kills, and his subsequent hatred for, and redemption by Gandhi.

Megha Dhaka Tara goes even deeper. Here, the Partition is never seen, only its effects felt. As a family tries to cope with migration, losing their property and roots, their identity, and having to make ends meet in a slum in Calcutta. Of lost dreams, lost lives, lost prestige. Neeta sees her family breaking up, even as she herself is being consumed by tuberculosis. Shankar, her brother, leaves, returns, leaves, returns, finally to see the only person he really cared about, dying. Truly, Neeta is the star whose brilliance is shrouded by the cloud of Partition. Megha Dhaka Tara doesn’t need to show blood and gore, but it is all about violence too — the violence of a colonial master playing with the life and fortune of people it has been lording over for 300 years.

***

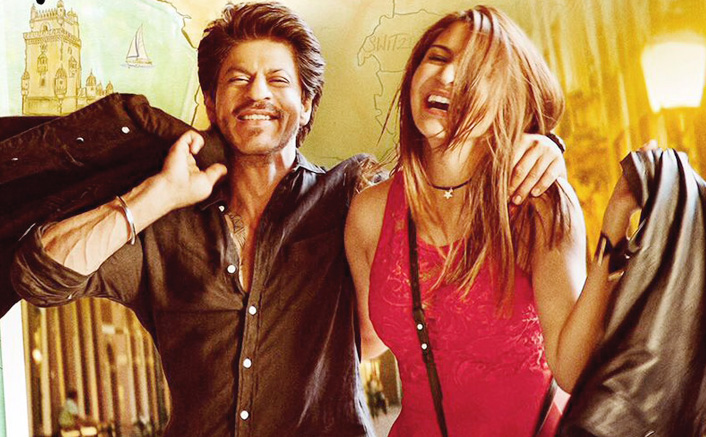

Viceroy’s House uses a common technique of a love-story set against a larger backdrop.

While big political fights and divisions go on upstairs in the Viceroy’s room, downstairs, Jeet (played by Manish Dayal) and Alia (played by Huma Qureshi) try and figure life and love out. Even as their friends and families — Hindus and Muslims — come to blows over the question of Partition. There is never any warmth, never any real traction in the Alia-Jeet romance. Alia is worried but surprisingly calm about the whole thing, Jeet is not sure who deserves his love more: Alia, India, or Lord Mountbatten.

***

Chadha’s script tells us that there was larger geo-political reasons behind the Partition. That much is true. In the Great Game between Britain and Russia — over Afghanistan, India. But by the time of Indian Independence and the Partition, Britain was spent as an Imperial force, and the Great Game had shifted countries, objects, and powers.

But Chadha’s story — based on a book by Narendra Singh Sarila, who worked under Mountbatten for a brief while — tells us that it was current, valid, and highly influential in deciding on the Partition, and further, even the border that cleaved one country into two.

How much of this history is true? Or is it, indeed, verifiable?

Lord Mountbatten, the historical figure, is a complex man on whom much of Partition’s death is blamed. His hurried, rushed-through plan to divide India, his decision to appoint Sir Cyril Radcliffe — who had no previous India experience, his complete refusal to talk to Jinnah of Gandhi’s idea of a Muslim League-led central government, his moving forward the date of Independence from June 1948 to August 1947 — all caused the deaths and violence, led to the deepest scars in modern history.

Recommended

The Radcliffe line — the final border between India and Pakistan — was decided based on census figures. And some final, last-minute negotiations by both Nehru and Jinnah. There were lawyers from either side, with Radcliffe himself a lawyer. But none of them had spent any time on the land they were about to cut up. There were no farmers and workers, no women and children, who could tell the commission that the line they were drawing, would run through their house, their land, their village, their lives. It was decided by a committee and in a room removed from the people it would affect.

Translating lines drawn on paper, to lines drawn on sand is about as cruel, heartless, and violent as you can get. And Mountbatten, who pushed for an early settlement, who accepted his role as Viceroy on the condition that it would be over and done with at his convenience and his timeline, not on the timeline of a subcontinent about to be broken up, is the cruelest of them all.

But Chadha’s Mountbatten is merely a well-meaning man caught up in the moment, who is being played by these incompetent Indians, and the conniving British. It feels like an apology that Chadha makes to her adopted homeland of Britain.