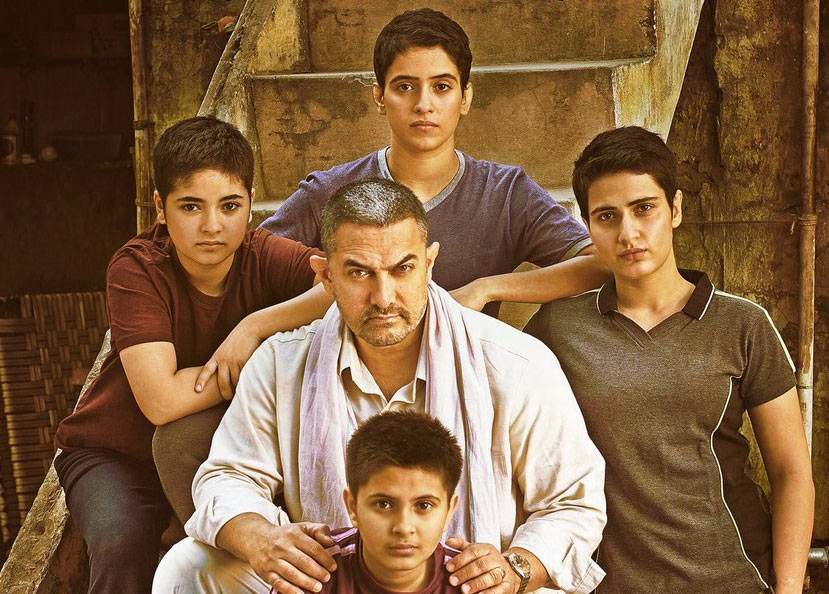

How did Aamir Khan’s Dangal, a simple sports film about a father training his daughters in wrestling, become so popular in China? And what does it mean for the Indian film industry and the Chinese box-office?

The recent Doklam standoff showed just how volatile relations are between India and China – one expert called it “seismic”. Neither country wanted a wider conflict. Eventually, both backed off. But this one crisis had “disturbed irrevocably” the status quo of three decades of Sino-Indian relations, said political experts.

So when Prime Minister Narendra Modi goes to Xiamen for the September 3-5 BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) Summit, it’s going to be awkward.

But there’s one thing he and the Chinese can find common ground on – Aamir Khan’s film, Dangal (or Shuai Jiao Baba – Let’s Wrestle, Dad in China).

Aamir, certainly, didn’t think he would become India’s most popular export to China.

When PK and 3 Idiots became big in the Chinese film market, Aamir had said, “In my wildest dreams I never imagined it (would do this well in China).” Asked if there was pressure to work on making films for foreign audiences, he said he didn’t know how to make films for anybody else:

“If I were to look at Bihar as a market, and maybe add an item number to the film, then look at China and think of an education angle, I’d end up with a khichdi.”

But then came Dangal, which released on May 5 in China and made Rs 757 crore as of August 29, overtaking even its India box-office earnings (Rs 387 crore). In fact, Dangal’s China collections are a big reason why it’s likely to cross SS Rajamouli’s film Baahubali 2’s global collections.

Earning 233.93 million yuan ($32.46 million) over its opening weekend, Dangal topped the Chinese mainland box-office charts, surpassing even the Hollywood blockbuster Guardians of the Galaxy Vol.2′s take of 128.81 million yuan.

It now ranks as the 12th most popular film in China. Ever.

This, despite the fact that the Chinese government allows only 34 non-Chinese productions to release each year.

Is this a sign of China’s growing fascination with Bollywood? Or is it a reflection of economics and government policy?

***

A Numbers Game

Industry experts attribute a few key factors to Dangal’s success, only some of which have to do with the film’s storyline, or its cast.

In 2011, China had only 9,000 screens. Today, thanks to the initiative taken by the Chinese government, it has around 41,000 active screens. In contrast, India is seeing a decline – from 12,000 screens seven years ago to about 10,000 now. A major reason for this, say analysts, is that while multiplex chains like Inox and PVR have been adding 150-odd screens each year, single screen theatres, especially in rural and small town India, have been shutting down.

Utpal Acharya, founder of film production, distribution and marketing company Indian Film Studios tells Livemint, “With 41,000 active screens, Dangal’s equivalent of China would release in at least 25,000-30,000 screens. The smallest release for an art, non-commercial film would be 3,000-4,000 screens. In India, our biggest films release in 4,000 screens.” In fact, Dangal released in 9,000 screens in China. But that is still nearly twice as many screens as in India.

The concern with expanding screens in India is not new, but possible solutions (like converting single screens into multiplexes) aren’t always viable. Only two years ago, Inox Leisure CEO Alok Tandon told Business Standard, “Not all single screens can be converted into multiplexes. They are usually on a single plot of land, and underground parking, open areas around are all requisites.”

And many blame multiplexes for the destruction of the good old days of popular single screens, including historic theatres like Metro (1935) and Globe (1922) in Kolkata and perhaps even the Regal (1933) in Mumbai.

But is the solution for Indian producers more screens and more multiplexes? The advent of online streaming platforms like Amazon and Netflix poses a sizeable threat to theatre chains – and might make the Indo-China screen imbalance a moot point in the future.

***

Making ‘Khichdi’ For The Chinese

In fact, Chinese film experts attribute the success of Dangal to the content, which was so gripping, that (as reported by a Chinese outlet) it put bladders on hold, put Chinese films to shame, and created a national debate among feminists.

Film critic and Tsinghua University professor Yin Hong famously said that the film had put Chinese films “to shame”. She said, “This should be a lesson for domestic Chinese films. China has many sports champions but not a single good sports film. This is something worth thinking about.”

And director Feng Xiaogang, who is known as the Chinese Spielberg, said he, “Watched the film with some 20 friends. When it finally reached the closing credits, a couple of them sprinted out to finally use the toilet. The opinion was unanimous: A good film!”

Meanwhile, feminists in China – as in India – were divided on whether the film was about the girls’ success, or yet another instance of the father imposing his will.

Unlike other parts of the world (like the former Soviet countries, Russia, the Middle East, and some African countries), Indian films weren’t really big in China. At least, not until another Aamir Khan film came along.

Nargis was a familiar name in China, thanks to the popularity of the Raj Kapoor classic Awara. But that was back in 1951. The next big hit was over 50 years later, with 3 Idiots in 2009. Shah Rukh Khan’s My Name Is Khan (2010), Nikhil Advani’s Delhi Safari (2012), and Dhoom 3 did decent business (Rs 50 lakh, Rs 10.65 crore, and Rs 24 crore according to these estimates).

Then PK blew it away with collections worth Rs 123.

Meanwhile, Baahubali: The Beginning released in 6,000 screens, but only made about Rs 7 crore in China. And no one realistically expects the sequel to overtake Dangal’s collections.

As Hong points out, China has a lot to learn from Indian films. Hong praised Dangal’s “artistic level – from the script-writing to the actors’ and actresses’ performance, and from the pace to the musical score – is amazing.”

Aamir himself felt the film’s popularity was due to what he called emotional resonance: “The reason it has become so huge is that the Chinese connected on an emotional level with the story, the characters and the important moments of the film.”

What’s interesting is that Dangal is hardly the run-of-the-mill Bollywood fare. There’s no Salman Khan-style torso baring male hero, romancing sexualised and glamorous heroines.

There’s just a determined, dominating father and highly obedient children.

And that, some experts said, is precisely why it resonated with a Chinese audience, where parents are very involved in their children’s education. In fact, Tan Zhen, a Beijing Film Academy professor of Indian film, told Global Times: “This story is very Chinese. I don’t think it will resonate as much in countries such as the US.”

And Aamir had worried he would end up making khichdi for Chinese audiences.

***

This contrast between Dangal’s success and Baahubali’s fate in China is going to be of great interest to Indian filmmakers, as they figure out tweaks that will appeal to the Chinese market (such as casting a Chinese actress, as Salman Khan’s Tubelight did). Meanwhile, many Chinese producers are working out co-production ventures with foreigners. This is one way they can circumvent the government restriction on outside films.

And co-production is something that film industry leaders are very interested in.

With each year, the US box-office market has been rapidly declining, even as the Chinese market (second behind the US) has been rapidly increasing (from less than one billion yuan in 2003 to 44 billion yuan in 2015).

Experts estimate that China will in fact overtake the US. As one analyst writes, “The question of whether China can compete with and potentially exceed the US box office is becoming more a function of “when” than “if” at this point”. Especially in a situation when American big-budget films continue to “struggle with US audiences increasingly burnt out on sequels and franchise properties.”

And further, while the US and Europe has an ageing population, China’s demographics indicate a robust cinema-going population. According to a 2016 estimate, the biggest movie-going category by age in China were people “between the age of 21-30, with the 25 and under demographic showing very high enthusiasm for films.”

***

Recommended

For China, leaning on India to counter balance its relationship with an unpredictable American administration makes sense. For Indian producers, (like Eros International, a major Indian film studio which launched a number of co-productions with China), teaming up with China makes perfect economic sense. (In fact, the Chinese government’s official submission to the 89th Academy Awards was Xuanzang, a biopic co-produced by Eros.)

But, as Professor Ying Zhu, a New York-based expert on the Chinese film and media industry tells The Diplomat, India will need to remain cautious.

“If Indian films grow to be dependent on the Chinese market, then Indian filmmakers would inevitably exercise caution in what pleases both Chinese censors and audiences,” said Professor Zhu.

Ultimately, the situation at Doklam and future tense stand-offs may remain unaffected by Indian films, but one thing is certain – big money is at stake; and that is something both Indian and Chinese policymakers will want to consider.

*****