From getting his chosen cast on board and creating the characters of Major Bala and Meenakshi, played by Mammootty and Aishwarya Rai, and book adaptations, to the time Irrfan visited him, hear it all from the cinematographer-director Rajiv Menon in this interview with Silverscreen India

***

Twenty years ago, a film that might seem an impossible project today, released. It had Mammootty, a top star from Malayalam; Ajith, a Tamil actor who was fast becoming a star; Tabu, an actress who’d made her mark in films by Gulzar and Mani Ratnam; Aishwarya Rai, a Miss World; and Abbas, a Tamil actor whose very presence had girls in a tizzy. Add to this mix, Bharatiar’s poetry, music, and some Sense And Sensibility. That, for you, is Rajiv Menon’s Kandukondein Kandukondein.

Two decades on, a conversation with Menon begins, interestingly, over how the oat, date, and fig crumble he put in the oven at 2 pm turned out in time for tea. But that’s how it is usually with Menon. Some prose, lots of poetry, books, music, films… all make their entrance. Much like Kandukondein, which had its protagonists straddle many identities. There was the soldier turned floriculturist, the educationist turned IT professional, the US-returned engineer turned aspiring filmmaker, a girl lost in a world of her dreams becoming a singer, a poetry-spouting businessman…

Excerpts from an interview:

What was the genesis of Kandukondein…?

During a walk with Mani (Ratnam), I was telling him how different the lives of my brother and I turned out. How our lives changed after the early death of our father, the decisions we took, the consequences. I was a quizzer and into cricket, but decided to be an artist. My brother who was into art and poetry focussed on academics, came first in Madras University in his Masters and became an IRAS officer. Mani told me why don’t you make a film about this.

Long before this, I’d read Jane Austen’s Sense And Sensibility and had seen the film too. I re-read the novel, and while making plot points, wondered if I could move them about a bit and make it about people leaving their home… what would happen. Some scenes and characters entered my head and I kept adapting them. I wondered what kind of character would create great instability in a home, what I could do to replace the landed gentry, and the world of tea parties of Sense… It was not a Dickensian world. Even in Sense, there are a lot of things such as honour, integrity, and goodness… Some characters wrote themselves: the assistant director searching for a location, the poetry lover… producer Thanu said it sounds interesting and that we should go ahead. I dictated the scenes and the dialogues I’d thought of in Malayalam to Sujatha Sir, and he got the first half of the film ready in one burst. Everyone seemed to like that. We knew something felt right about it. Every house has a story of family strife. Everyone says they’ve fallen into poverty. There seems to be a sense of loss of a glorious past and we decided to turn that into a rural-urban story, with a family coping with anonymity in a city after recognition and respect in a village.

I wanted to remove them from a set-up where patriarchy felled their existence and bring them to the city where they change and grow. If you see, everyone is journeying in the film. They’ve all moved.

Tabu and Aishwarya

Do you visualise being able to make such a film now, where you have big heroes and heroines, but no ‘mass’ moments?

Ah, interesting. I think it’s difficult to bankroll a film like this now. It’s not what you’d call a ‘masculine’ film, the principal characters are women, and that must have been a shock even then. I think the enduring appeal of the film is because few hero-driven films have strong heroines.

It was almost like you foresaw a lot of careers in that film… engineers becoming directors, which is commonplace now, the IT industry…

No one then knew software would become so big. I’m so glad it did, because it brought about equality of sexes, thanks to the same pay scales. The sector saw more love marriages, which effectively did its bit to smash caste and class divides.

Both the heroines came with very distinct characters. They had a mind of their own, sought respect.

Yes, they shift from a rural background, where they cross level crossings to go somewhere and move to a place with glass buildings and conference rooms; it’s not easy. One moves from being Principal to a telephone operator. The other becomes a chorus singer and drowns in her sorrow. Everyone asked how I could make a Miss World fall down a drain hole. For me, it was a trial by fire and the sisters emerged stronger people, burnished by experiences. One realised what love means, and the other was willing to move away if she did not get an apology.

I wrote Sowmya and Meenakshi at a time when heroes had still not become larger than life and where a woman was not seen as someone who pulled the man down. I see a general decline in women characters now; filmmakers can have their reasons. However, I believe a strong drama needs strong women characters to work. Be it Satyavan and Savithri, the Mahabharata, The Ramayana, or Nala Damayanthi, women are central to the narration. So, when you write a family drama, it is important to see both the female and male points of view; modern Tamil dramas are no longer about the man and woman.

If there’s something you could change in the film, what would that be?

I’d probably write the poetry-speaking Abbas’ character with greater depth. Some were angry with him, for leaving Meenu. But, he had his reasons. He had integrity. Thomas Hardy’s tragedies will always have an outside element, an act of God that will result in a great change, unlike the tragic human flaws in Shakespeare’s works. I was inspired to write that character because I would see people queue outside the offices of the then-defunct Royapettah Benefit Fund and Alwarpet Benefit Fund. To see old people waiting for their money did something to me.

The film is probably one of the few to speak about someone who served in the IPKF in Sri Lanka…

Our cinema has become very jingoistic and nationalistic. And while army action in Uri and Kargil is celebrated on-screen, our people dying in a foreign land is not even acknowledged. IPKF was our Vietnam moment. I wanted to examine what happens to a forgotten soldier from a forgotten war; they too die in honour, show valour, experience pain and sacrifice (A dialogue in the film says: what’s worse than death is being forgotten: Maranatha vida mosamanadhu ennadhu-nu theriyuma? Marakkapadradhu). I wanted to speak about the human side of that conflict, about the emotional damage that happens to those who go to war. The film discussed PTSD before it became a thing in movies.

The inspiration for the Army angle was a young Para commando I met on a train back from Kochi. He was telling me terrible stories of the war, he expressed sadly, that the war was going badly, he could come back in a body bag. He would call me when he would pass through Chennai.

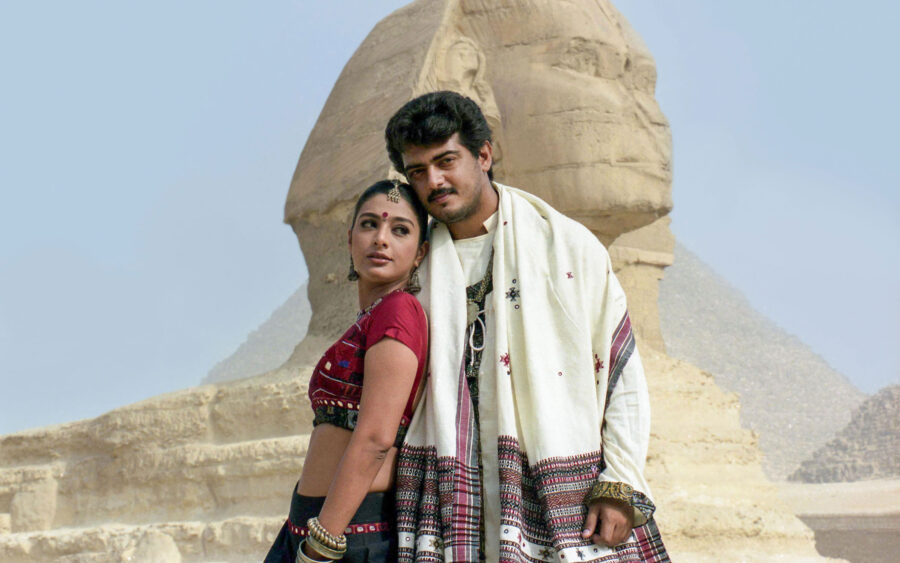

img056 k k

One day, the phone rang. My commando acquaintance had been injured and I went to visit him at the St Thomas Mount Military Hospital. He had a lot of pellet injuries and lacerations. Next to his bed was a jawan from his unit who was also injured; his leg had been blown by a landmine and amputated. The Para commando was lucky to be alive, I was shocked and speechless.

The sum of those experiences was Major Bala. Mammootty really enjoyed playing that raspy character.

You’re one of the few new-age filmmakers who attempted to adapt a book to film, and successfully. Are you looking at something similar again?

I keep trying to read and see what I can do with the material. Great literature is not easy to translate. You need to condense a story into three acts and see the graph of the characters clearly. The modern novel is actually pretty anti-filmmaking because the three-act structure with a happy or sad ending is boring for most people. Writing the screenplay for a film is very different vis-a-vis writing a novel.

Eight years ago, I tried adapting Fiddler On The Roof, with a focus on the Kashmir situation and the exodus of Pandits. Amitabh Bachchan was to play the old man, but it fell through. The production company in Bombay folded up.

I still feel that there is a good film in Aravind Adiga’s The White Tiger (it’s already slotted to be a Netflix film, by someone else!) I found Srinivas Reddy’s Raya (about Vijayanagara’s Krishnadevaraya) absolutely fascinating. You can’t put it down; it’s like seeing the man in flesh and blood and there’s a great emotional connect. I am constantly looking for a deeper insight into a fictional character, which is why I like Malayalam writer Syam Pushkaran of Kumbalangi Nights fame. A lot of Indian cinema has taken a complete U-Turn from the kind of progressive middle-class urban sensibility it once promoted; there’s no balance between the feminine and the masculine.

(This brings us to speak of the late Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Became Air, and how I always imagined Irrfan playing the role if it ever got made as a film, and then…)

Recommended

In the early 2000s, Asif Kapadia’s Irrfan-starrer The Warrior was on a British Council tour of cities, and I told him I really liked it. Two weeks later, Irrfan landed in my office saying he wanted to work with me. I was then writing Spin, about Anil Kumble and his beautiful bond with a boy with muscular dystrophy. He said he would do it. And then, Sanjay Leela Bhansali wanted to do Kandukondein in Hindi, and we thought Irrfan could do Major Bala’s role. He sat one whole afternoon in my office discussing it. Both did not eventually work out. Then, Life of Pi happened and he became a huge star. I felt terrible that an actor came to me to work with me, and I could not use his talent. It was my ‘Sowmya’ moment. Sometimes, some stories don’t work. Due to some reason – self-doubt, being too critical, or because you’re not desperate for money because you have some other source (Rajiv has revenue from advertising). That time will never come back. Some nights I wake up in cold sweat, castigating myself for not working on something. Then, when dawn breaks, I tell myself I can never make a film I don’t believe in. Like Somerset Maugham says in The Razor’s Edge: “Death ends all things and so is the comprehensive conclusion of a story, but marriage finishes it very properly…”

Stories like Kandukondein conclude in marriage, which is a very cathartic feeling. I’ll always feel sad I never worked with Irrfan. In my book, Irrfan and Dhoni represented meritocracy in India, who rose to the heights from adversity and behaved in an exemplary fashion.

You’re also one of the few directors who’ve gone beyond Aishwarya Rai’s stunning beauty, which the camera usually captures, and peeped into the performer in her…

Meenakshi had to be beautiful and tempestuous and the Aishwarya I know from advertising is someone who is Meenakshi in many ways. I share a good equation with her thanks to some commercials we shot together, and when she had to choose between Minsara Kanavu or Iruvar for her debut, I told her to choose Mani’s film, because he was a better filmmaker, and I was making my first film. She was grateful I did not put her in a dharmasangatam (moral quandary) and when I went to her with Meenakshi, she said she would listen to her heart and told her mother to somehow fit in the film. In real life, she’s a very curious impulsive person and not the diva you see on screen. She had a normal middle-class existence. She would remember and warmly ask for Rosy, our cook, who made aapams for her when she shot for a scene in our flat for Kandukondein, and hug her. She usually stiffens when the camera rolls, and I had to keep telling her to relax and be casual. She got into that vibe very fast. Ajith, for instance, is very relaxed in front of the camera. Hurt and pain come naturally to Tabu. Each artiste has a quirk and when it goes with the character and if they get that right, the film works.

AjithTabu-KK

Did you expect to see the #

Oh no. In fact, I never expected to get this old. I can’t see myself as a 55-year-old. My father died at 41, and a doctor told me that I might take after him. I was convinced I would die at 40! Glad I’ve lived.

Featured image of Rajiv Menon courtesy: JFW