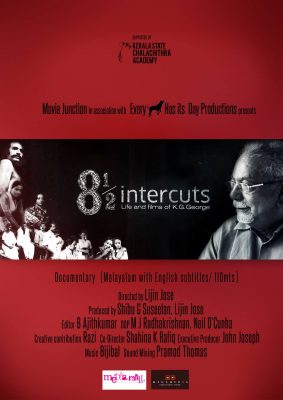

8 ½ Intercuts: Life and Films of K G George, a documentary film directed by Malayalam filmmaker Lijin Jose, and produced by Shibu G Susheelan and Lijin himself, premiered at the 10th International Documentary And Short Film Festival Of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram, on June 18.

In the opening sequence of the documentary, KG George, now a frail old man, watches a black and white film on his laptop, grinning like a child. It is 8 ½, the 1963 Federico Fellini classic about a director’s existential crisis. Later, we would hear him shake his head adamantly and say, “I can never make a movie again”, as his wife, Selma, a yesteryear playback singer, reiterates that he can, if he ‘puts his heart into it’.

kg george

No one minces words in this 120-minute long film. The master is praised, criticised and even lambasted by his peers, collaborators, kin and admirers, and he approves of them all with a smile. He talks about his early inspirations that led him to make some of the best psychological dramas in the country, and hesitantly hints at the fissures and conflicts that forced him to hang up his boots.

George, a gold medal-winning FTII (Film & Telvision Institute Of India) graduate, has bagged nine State Awards, one National Award, and the coveted JC Daniel award in his career. His oeuvre has films like Irakal , Yavanika and Adaminte Variyellu which are regarded as classics. His films stood out among the commercial cinema of the 70s and 80s, for their distinct form and themes, probably an influence of FTII. He, along with filmmakers like Adoor Gopalakrishnan, G Aravindan and John Abraham, are known for pioneering the new wave cinema in Malayalam. Yet, George’s works as a filmmaker is largely overlooked, especially outside of Kerala, as compared to Adoor Gopalakrishnan and Aravindan.

Lijin, who has directed two feature films (Friday and Law Point) considers 8 ½ Intercuts: Life and Films of K G George as the most important work in his career so far. An ardent fan of the master filmmaker’s works, he spent nearly four years researching the subject, and making the film.

*****

In the documentary, Lijin chooses to keep the narrative objective and linear, compiling interviews that he conducts with George, Selma, his collaborators like actor Innocent, cinematographer Ramachandra Babu, and actress Jalaja, and his contemporaries like filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan and film critic CS Venkiteswaran. Members of the younger generation of Malayalam cinema – actor Fahadh Fazil, directors Anjali Menon and B Unnikrishnan, and actor-director Geethu Mohandas – too make an appearance. The interviews are inter-cut with visuals from his remarkable films such as Irakal, Yavanika, Mattoraal and Mela.

Interestingly, the voices conflict at times, especially on topics such as George’s treatment of human suffering and feminism on screen. George, who portrayed women with brilliant sensitivity and progressiveness in his films, was an insensitive philanderer in real life, says Selma, fuming, as she sits by his side on a patio chair and talks to the camera. Her relationship with George is complex, much like that of the characters you would find in his films. Lijin, with a touch of mischief, cuts from Selma and George to a footage from Fellini’s La Dolce Vita where a couple argues about love. “What have I done to be treated this way!…You don’t love anyone!” says the woman in the film. A part of the audience breaks into a feeble chuckle.

George talks to the camera with palpable innocence, and sometimes, with zen-like humour and calmness. “I made many movies that shouldn’t have been made,” he says. His words do not reflect any regret, but an honest admission presented like a matter of fact.

The documentary also reminds one of the golden period of Malayalam cinema that the 70s and 80s were. There are delightful mentions of the ‘Pune House’ in Chennai (named after FTII which is the common alma mater of many of its tenants), which was an informal hub of south Indian filmmakers, technicians and actors.

Films of George and his peers broke the existing conventions of filmmaking. Their films rebelled against popular notions of morality without any fear. George’s Mattoraal had a heroine who leaves her husband and a quiet and dull middle-class existence, for a lower-class bike mechanic. The film doesn’t frown at her, rather, sympathises with her. “In Mattoraal, there is no attempt to save the middle-class dignity by quietly sending the wife back to her husband and reconciling. The film is brutally honest and bold, unlike what later films like Chinthavishtayaaya Shyamala did,” argues B Unnikrishnan. Another movie of his, Adaminte Vaariyellu has a unique climax sequence where a bunch of women break free from a rescue home where they had been kept, and run to freedom. George then decides to pull down the fourth wall in this scene. The running women are seen pushing aside George and his camera crew, as they stand watching aghast.

The docu-film also touches upon the dark side of the era when many talented artistes vanished from the centre stage after losing the plot of their life. “People might blame me for encouraging Balu Mahendra’s affair with (actress) Shobha. (Balu Mahendra was the DoP for George’s Ulkkadal, which had a young and talented Shobha playing the female lead). But at that point of time, I looked at their affair as something extremely beautiful and gentle,” says George in a voice that mirrors gloom and regret.

There is gleaming poignancy in the part where he recalls the time Balu Mahendra generously helped him with shooting equipment for Lekhayude Maranam, Or Flashback, a film which is allegedly based on the disastrous love story of Balu Mahendra and late actress Shobha. “He knew I was making a film inspired by the death of Shobha,” says George, his voice faltering.

Recommended

In another instance, he recalls his final meeting with his first flame, in a garden in Pune. “The golden light of the setting sun had spread everywhere, and I watched her walk away into a silhouette. I adore that image. I want to remember that on my death bed,” he says. One can’t help but spot the fantasy quality of this image, polished by time. The man who spent much of his life burrowing into the dark layers of human consciousness, is perhaps taking solace in this sublime memory.

Most of all, Lijin’s documentary doesn’t bear a tone of self-righteousness. The scars and flaws of the filmmaker are untouched. In fact, you see that he wears them on his sleeve, rather proudly. Would the brilliant artiste who cut open the mind of his characters and bared the demons that lived inside, be scared of darkness?

*****