It’s Oscar season. On September 23, an Amol Palekar headed Film Federation of India jury nominated the Marathi film Court, directed by Chaitanya Tamhane, as India’s official entry to the Foreign Language Films category of the Academy Awards. The film tells the story of an ageing folk singer, charged with singing an inflammatory song, and inciting the suicide of a sewage worker. Court has already won two awards at the 2014 Venice International Film Festival. Meanwhile, as we follow the film’s progress at the Oscars, here’s a look at India at the Oscars, the marketing madness around the awards, and the status of the ‘Foreign Language Films’ category in today’s globalised world.

*****

Awarding a non-American country for a single film has become the subject of debate. Unlike other Oscar awards, the Foreign Language Films award is considered an award for the submitting country, not for an individual artist. Many argue that it’s meaningless to retain this award section, since co-productions from different countries are quite common with the growth of communication technologies. For instance, this year China’s official entry to Oscars is Wolf Totem, a Chinese-French co-production directed by Jean Jacques Annaud, a French auteur. In fact, Deepa Mehta’s Water (2005) was Canada’s official submission.

In 2014, French distributor Vincent Maraval, of Wild Bunch, told Variety that the Academy’s foreign-language rules are “unique, specific and make no sense. He was referring to the Academy’s refusal to accept the critically acclaimed Blue Is The Warmest Color as France’s official entry, citing that the film’s France release date falls beyond the Academy’s deadline. Foreign films have different guidelines, such as a mandatory release in the home country, exhibition for at least seven consecutive days in a commercial movie theatre, and a different release deadline.

Another problem is the language requirement. The film has to be in a language other than English, and the Academy is very strict about disqualifying films with too much dialogue in English.

Controversially, until 2006, films had to be in the official language of the country – preventing films made in indigenous languages and languages of diasporic communities from competing.

apocalypto

And then, there’s the very definition of a country.When Humbert Balsan tried to submit the critically acclaimed Palestinian film Divine Intervention (2002), he was told that the State of Palestine was not recognised by the Academy, and hence the film couldn’t be accepted. The Academy faced accusations of double standards, given that they had accepted films from other political entities, like Hong Kong.

Marketing Madness

“What a thrill. You know you’ve entered new territory when you realise that your outfit cost more than your film.”

– Jessica Yu, Best Short Subject Documentary for Breathing Lessons: The Life and Work of Mark O’Brien, 1997

With a lengthy three-stage scrutiny process to select the winner, the publicity campaign becomes all important. First, six of the nominated films are proposed by Academy members and another three by expert advisory panels, who may not be Academy members. Of the nine long-listed films, five nominees are short-listed by a Foreign Language Film executive committee. The final voting is done by a special committee of 750. A campaign has to be built around the film to draw maximum number of Academy members to the screenings.

Publicity campaigning at Oscars is exorbitant. According to a New York Times report, a decent campaign costs around $50,000. According to a seasonal agent, “The really good ones, from countries like Belgium or Germany, cost around $100,000. And the money is usually eaten by the ads (in papers like Variety and The Hollywood Reporter). A couple of half-pages and a couple of full-page ads, and it’s one third of the budget.” For film makers from smaller, third world countries, this campaign process is a hard nut to crack.

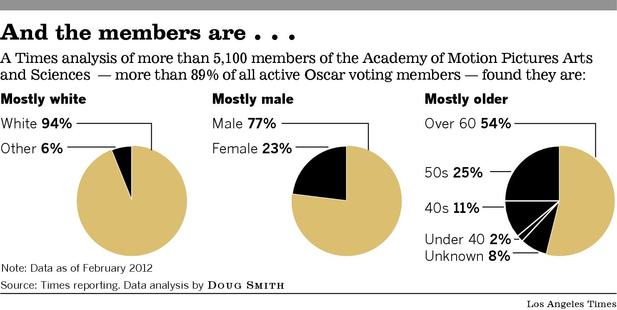

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the importance of the campaign, most awards have gone to European films.

Since 1947, of the 67 awards handed out by the Academy to foreign language films, 55 went to European films, six to Asian films, three to African films, and three to films from the Americas. The leading Oscar-winning country is Italy, with 11 awards.

In 2009, stand-up comedian and actress Mo’nique controversially refused to campaign for the award, publicly speaking questioning Oscar campaigning. Being a relatively unknown actress, several experts felt that would be the end of her Oscar journey. But, surprisingly, Mo’nique went on to win the supporting actress award, a turn of events she gratefully acknowledged in her acceptance speech, “First, I would like to thank the Academy for showing that it can be about the performance and not the politics.”

India at the Oscars

“This is a terrible mistake, because I used up all of my English.”

– Roberto Benigni, after winning his second Oscar of the night for Life is Beautiful, 1999

A recent Indian Express report says the Centre is working on a plan to build a corpus fund that will be used to finance full-fledged publicity campaigns for India’s entries in the run-up to the Academy Awards. According to the report, a proposal was submitted by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, and received a big thumps-up from Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In the past, many celebrities, including actor Aamir Khan, whose Lagaan was India’s official Oscar entry in 2002, have pointed out the lack of networking and publicity campaigning as the main reasons for the poor performance of Indian films at Oscars.

Directors of the nominated films depend on publicists who handle the campaign, and publicists don’t come cheap. Publicists are people who make it their business to know the Academy members inside out. They know where to advertise the films and how to carry out the screenings. A Quartz report quotes film maker Geethu Mohandas, whose Liars’ Dice was India’s official Oscar entry last year:

“Each publicist will have at least five to six films that they represent all over the world. And it’s not like we choose them. They choose us.

They themselves do a certain amount of homework. They watch the film and then they decide if they want to be associated with this particular film.”

Lagaan_Soundtrack

Lagaan was made on a budget of Rs.25 crore, while Court has a shoe-string budget of Rs.3.5 crore. A small film like Court cannot possibly match the amount Aamir spent marketing Lagaan, thirteen years ago. To that end, the India government’s latest efforts to form a corpus to push the country’s small-budget films at Oscars is indeed, a laudable gesture.

Indians at the Oscars

India has never won an Oscar. But Indians have.

- Bhanu Athaiya was India’s first Oscar winner after winning the Best Costume Design award for Gandhi (1982), along with John Mollo. She’s worked with filmmakers like Guru Dutt, Yash Chopra, Raj Kapoor, and Ashutosh Gowarikar

- Satyajit Ray was given an Honorary Oscar for Lifetime Achievement in 1992. Ray was in hospital, dying, at the time. He gave his acceptance speech, crediting American films as a major influence, from the hospital bed, via live video feed. Audrey Hepburn presented the award.

- The British film Slumdog Millionaire (2008) won eight out of ten Academy Awards. Two of those went to AR Rahman for Best Original Score, and the Best Original Song (‘Jai Ho’).

- Kerala’s Resul Pookutty, sound designer, editor and mixer, also walked away with an Oscar that night – the Best Sound Mixing award.

- And the night wasn’t over for Indians. Iconic lyricist Gulzar joined Rahman for the Best Original Song award.

*****