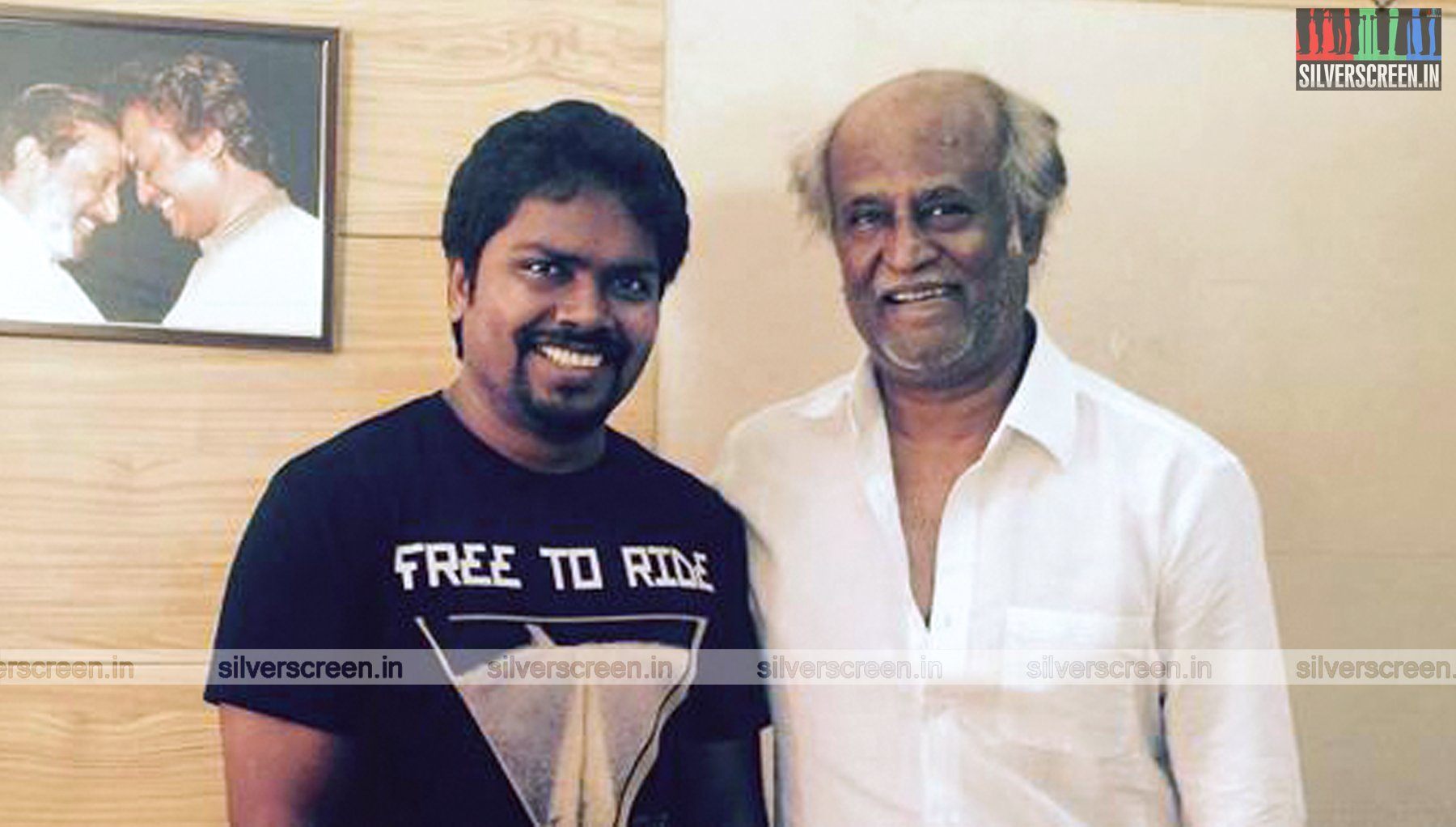

Renganaath Ravee is in Ernakulam, busy preparing for his wedding. “So little time, and so much to be done,” he huffs. An important feature film project – the details of which he is hesitant to spill – might take off any day this week. Among other projects he’s got lined up are filmmaker Lal Jose’s Nalpathiyonnu, starring Nimisha Sajayan and Biju Menon. In an exclusive interview to Silverscreen, the two-time Kerala State Film Award-winning sound designer talks about his career, in films that spans over a decade – across the Hindi, Tamil and Malayalam film industries – on using sync sound, and returning to his hometown Kochi for an upcoming documentary directorial.

In December 2018, Renganaath Ravee, 38, started work on a long-time dream –his first directorial – a documentary about Kochi, the place he grew up in. The film, titled Pappanji (an indigenous term for Santa Claus), delves into the coastal town’s unique Carnival that takes place annually in the last week of December. The film is produced by a new banner, Whiz Movies, that Ravee started recently with his friend Nisha Mathew.

“It is in post-production now,” he says. “I moved away from Kochi a long time back for work. A few years ago, I attended the carnival, and the idea for this documentary came to me then.”

Ravee started his career as a sound recordist at KJ Yesudas’ Tharangini Records in Thiruvananthapuram. In the mid 2000s, he moved to Mumbai to work in Hindi films, documentaries, installations and corporate films. His first feature film was Sarthak Dasgupta’s The Great Indian Butterfly, in which he worked as a sound editor. During his Mumbai stint, he collaborated with filmmakers such as Meghna Gulzar (A Pocketful of Poems, a short documentary on the works of Gulzar, and a promotional video for United Nations), Ram Gopal Varma (Agyaat), and Sujay Ghosh (Aladin).

In 2010, he made his Malayalam debut with Lijo Jose Pellissery’s directorial debut Nayakan. He has since been a constant in the filmmaker’s team. He’s also a part of Lijo’s Jallikattu, which will begin its festival circuit soon. His other notable works include Ennu Ninte Moideen (2015), which earned him his first Kerala State Film Award, Gautham Vasudev Menon’s Tamil thriller Nadunisi Naaygal, Jayaraj’s Pakarnnattam, and Joy Mathew’s Shutter.

The sound designer won the Kerala State Film Award a second time in 2017 for his work in Lijo’s Ee Ma Yau (The Funeral), a drama that discusses death, religion and paternity. Ee Ma Yau doesn’t have a background music track, save for the last five minutes, where a piece of music, composed by Prashant Pillai, is used to create an emotional impact. However Renganaath’s work is present through the film, even as his soundscape guides the audience.

“When people talk about Ee Ma Yau, they always talk about the sound of the wind, rain and sea. But I think it’s the soundscape of the crowd that lends the film a distinct identity,” he says.

The film was shot in Chellanam, a coastal village in Kochi, geographically similar to the place Renganaath grew up in. “I am familiar with the place’s language and culture. That helped me. Pouly (Valsan, who played a supporting role in the film) chechi and my father worked together for many years in theatre. Her Kochi dialect is spot-on. If you notice, people living in coastal villages speak a little loudly. I could bring such minute details of the region into my work.”

There is a certain sense of excitement in his voice as he talks about his work in Angamaly Diaries (2015). “For this film, we used the voices of more than 20 people from the area where the film was shot. It took close to 280 hours for the final mix. Only three-four sounds were used from my repository. The others had to be recorded. I went to a slaughterhouse for the scene in the film where pigs are hit with iron rods. It was such a strange experience to witness killing from close quarters.”

Jallikattu, he says, was challenging too. “We had to record a crowd scene in a field in Idukki. Each frame had close to a 1,000 people, and it took us two days to recreate the sound of that scene.”

Among the filmmakers he has worked with, he rates Lijo, Jayaraj and Bejoy Nambiar highly for their understanding of sound in mainstream cinema and its uses. “For the three films that Lijo did after Double Barrel, we completed sound at least a month before the release of the film. He makes sure that we are able to work without pressure. He is well-planned and works hard to get every aspect of his film right,” says Renganaath.

One of the major issues a sound designer faces in the Malayalam film industry is crunch. “Filmmakers take two years to work on the script or production, but spend little time in post-production, especially in the sound department. Sometimes, we get just two weeks or even less. I have had to quit many projects for this reason,” says Renganaath.

In many occasions in the past, cinematographers and sound designers working in Malayalam have spoken about the substandard infrastructure in Kerala’s theatres. In January this year, around the release of VK Prakash’s Praana, Oscar-winning sound designer Resul Pookutty said at a press meet: “I have travelled from Thrissur to Thiruvananthapuram watching Pranaa in various theatres to experience my work. Unfortunately, most of the multiplexes have disappointed me to the core with poor sound systems…”

Renganaath feels hopeful that with the rise of a more sensible audience culture, theatre owners will be forced to work on the infrastructure. “The audience has now started to understand sound. Ennu Ninte Moideen was done in Atmos, but a cineplex in Thiruvananthapuram played the movie in a screen not equipped with Atmos technology. In another incident, when I complained to a theatre owner about the bad sound quality, he shrugged, and said: ‘Why don’t you mix the sound to suit our infrastructure?’ It is disappointing, but I really believe our works will be saved and recognised if not now atleast later.”

Recommended

I ask him about the excessively loud and overstretched background score in some Malayalam mainstream films. “When the background score is used from the first frame to the last, with the kind of heavy orchestration that you hear usually in a full-fledged song, it is a problem. A loud background score can be used in instances such as a pub scene, but using background music to eliminate silence isn’t how it should be,” he says. There have been a few instances where he’s had to work closely with music directors too. “In films such as Amen and Ennu Ninte Moideen, my sound work was completed before the music director came in. It helped because he knew in which places I needed silence.”

Over the last few years, there has been a surge in Malayalam filmmakers who prefer to work using sync sound audio. There has also been a simultaneous rise in the use of plugins that replicate sync sound recording effect. “You don’t do sync sound audio because it’s fashionable or just to create reverbs. It is for the benefit of actors,” says Renganaath. “Sync sound recording helps capture the actors’ performances on the set without losing the essence. See how it worked in Carbon (2018), which used this technology excellently. You can see how it backed the performances.”

Sync sound recording can be an arduous task, especially in a country such as India, where the atmosphere is rife with different loud sounds. A few weeks ago, Renganaath Ravee worked in the Indian schedule of a Portuguese language film shot in Varanasi. “That was my first time doing sync sound for a feature film. We had to live-record a lot of Dhrupad music in the city’s cacophony, but the makers were determined to shoot only with sync sound.”

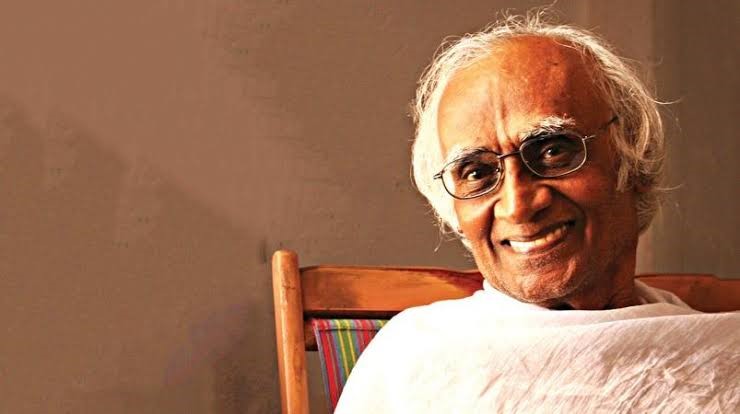

Among his favourite films that have exceptional sound are Vasthuhara, Piravi, Sathya, Guna and Kuruthipunal. “Vasthuhara was shot on sync sound in 1991 when no one had heard of that practice in Kerala. Even as a child watching that film then, I felt something was different about its sound,” he says. “In Bhadran’s Spadikam (1995), there is a scene in the second half where a minute sound effect of pulse is used to create a great emotional moment. Padmarajan’s Aparan (1988) has an excellent soundscape. The BGM score used in the film’s enigmatic climactic scene is so delicate. In Manichithrathazhu, it took just a gentle strain of Veena and a brief tinkle of an anklet to terrify us. What matters is the impact, and not the quantity of work done,” he says.

Renganaath continues to work in short films and student projects as he has always done. “I do them to just support new filmmakers. Whether its a feature film or a short film, it’s not the money or the star cast that matters to me, but the director’s passion towards the medium,” he says.

Talking about the time he was thoroughly disillusioned with the industry, he says, “It was a few years ago. I overcame it, so I can talk about it now. I was working on a project in 2015 that demanded a lot of effort. In the end, I was exhausted. It seemed like a never-ending phase. I rejected many offers during and after it. Finally, I quit this field. It was my first State Film Award that brought me back. Now, I am in a more peaceful space.”

The Renganaath Ravee Interview Is A Silverscreen Exclusive