Before taking the plunge into the world of indie feature films, Priya Ramasubban led a globe-trotting life. For over fifteen years, she made documentaries – long and short – for international television networks such as National Geographic, Discovery Channel and History Channel in over 29 countries. Now, her first feature film, Chuskit, based on a true story of a little girl in Ladakh, has won Gold at the recently concluded MAMI Mumbai film festival

In 2012, when Priya Ramasubban embarked on her debut feature film venture, Chuskit – set in Ladakh, a Himalayan region that falls in Jammu & Kashmir – she didn’t quite expect it to be a journey that would stretch over five years and many roadblocks. Nevertheless, it ended on a great note. In 2016, the project was selected to NFDC Screenwriter’s Lab. The film premiered at Giffoni Film Festival in Italy in 2018 where it won a special Amnesty International Award. At the 20th MAMI Mumbai Film Festival, the film won the Golden Gateway for the Best Feature (5-9 years) in the Half Ticket section.

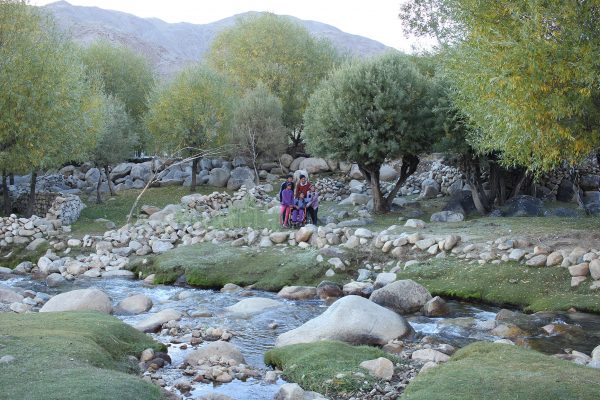

The film has a plot as simple as its protagonist Chuskit, a little girl of nine years living in a Himalayan mountain hamlet. An accident has rendered her paraplegic, bound to her bed by the side of a window that opens to the sight of the village lane and the playground beyond. The Ladakhi language film is heartwarming, centered around Chuskit’s unassailable dream to go to school and be ‘normal’. The rather straight-forward narrative doesn’t rely on melodrama, contrived situations or the rhetoric. Priya focuses on Chuskit’s struggles and community life in the mountain village. Besides the practical difficulties of going to the nearest school which is across a rocky stream, Chuskit has to fight and overcome the orthodox mindset of the adults around her who believe it’s best for her to accept her limitations and stay at home.

A Tamilian, Priya lives in Bangalore where she is steadily involved in numerous civilian movements for environment conservation and gender rights. Her sister, Vidya, lived in Ladakh for over 10 years, working among children with disabilities. “She has many bundles of stories from her life over there – especially about the struggles of being disabled in a mountain terrain. Her friend Sujatha wrote the book, ‘Chuskit Goes To School‘, based on a real story, and my sister wanted to make a film on it. When she couldn’t find a taker for a long time, she decided to give her documentary filmmaker sister a shot.”

Priya and her crew stayed in Ladakh for three weeks in the winter of 2012 to shoot the initial portion of the film. But the filming had to be stalled for a few years, and resumed in 2016. “I gravitate towards people wherever I go. I explore the place through people or with people,” says the filmmaker at the lobby of a Mumbai hotel where we sat down for a chat. ” I love the people of Ladakh. Their spirit, humaneness… Life isn’t really easy on those mountains.”

What drew you to this particular story?

Chuskit is inspired by a real story. The girl, Sonam, was born with paraplegia, and not caused by a fall as we see in the film. The grandfather in the film is an amalgam of every resistance she had to fight to go to school. The ending of the film is totally based on Sonam’s story.

I make films for National Geographic, Discovery Channel etc. I run a non-profit trust in Bangalore for environment, and I help women going through difficult situations. I help them file an FIR, fight legal cases and so on. I feel the issues on the periphery of everyone’s vision never gets focus. Here, a kid who wants to go to school cannot do so because adults haven’t figured out a way to get the child to school. So she has to lead a sub-par existence. I believe it’s our duty to enable those who can’t do things by themselves. Somebody has to step in to do something for those who can’t do things on their own.

The making of the film took several years. How did you make sure that neither you nor the crew lost faith in the project?

If you are a filmmaker of the kind I am, or someone doing socially relevant work, you need to have a tenacity – the ability to say “I will come back” when someone turns you down. I find it hard to take no for an answer. I began by raising money on Kickstarter. I raised around Rs 50 lakh in one month, with which I shot the winter portion. Around that time, my mother fell ill, and eventually became wheelchair bound. As her family, it took time for us to come to terms with the fact that her condition was permanent. Almost two years after the shoot, I started becoming conscious about the fact that people had trusted me with their money and I had to complete the film. I felt this huge responsibility. Immediately, I asked people in Ladakh to send me the child artistes’ pictures because that was another fear – Chuskit is supposed to be of a certain age. I was relieved to see that she was just about the right age.

Meanwhile the film got selected to NFDC Script Lab where it became much better, thanks to my mentor, Jolein Laarman, a Dutch writer-filmmaker. The Lab helped me procure some funds too. Call it serendipity, two founders of Wishberry, Anshulika Dubey and Priyanka Agarwal, got in touch with me and offered to do gap funding since they liked the project. They helped me raise the rest of the money.

What was the experience like to take a crew to a rough terrain like Ladakh?

We shot in two different villages in Ladakh, and had a tiny local crew, and others from Mumbai and Delhi. I had shot a documentary in Ladakh in 1998, and I learned my lessons there. That was a National Geographic series. We were shooting in Khardungla which is 17,500 ft above the sea level. A crew member from Tamil Nadu collapsed during the shoot, and was taken to an army base camp immediately. That incident stayed with me – the knowledge that a man could have died during shoot. So this time, I was thoroughly prepared. I had gender, health and safety guidelines handed over to everybody on set. After landing on the set, everyone had to lie down, and not be up for a day. Stay in their room, drink hot water – which increases oxygen in blood, have food. In short, nobody got sick this time.

How did you find the cast?

Jigmet Dewa Lhamo, who played Chuskit, proved to be a brilliant actor. To find the actors, we conducted a workshop with the help of my sister, and Mr Chetan Wangchuk who works with schools in Ladakh. At the audition, we asked kids to perform a scene where they had to sulk about the meal their mother served to them. While the rest of the children expressed their displeasure in words, Jigmet, decided to use facial expressions and body language. She was so natural, and it didn’t take long for me to conclude that she was the one I had been looking for. She wasn’t aspiring to be a professional actor. So while the film was put on hold, she became busy with school, learned Karate, and carried on with her regular life without any concern.

Ladakh, for outsiders, is an exotic landscape. How did you want to shoot the landscape?

I have used a fly-on-the-wall anthropological style, without focusing on the landscape beauty. Yes, it’s a beautiful place, but for the people living there, it’s home. They are not overwhelmed by it. We chose to treat it like that.

The film’s sound design is handled by PM Satheesh, a veteran from the mainstream film industry.

Perhaps my favourite part of the film is its sound design. PM Satheesh is a National Award-winning artiste who worked on projects like Baahubali. When a friend recommended his name, I was almost sure that he wouldn’t agree to work in my small film. To my surprise, we got along on the first meeting itself. Sitting with him in the mixing room was such a joy. Most people might not notice the beauty of his work in this film because it’s so gentle. Like the sound of leaves rustling and wind blowing.

That sounds like how you speak feminism through your film – gentle, unnoticeable.

In storytelling, I don’t like anything being shoved down your throat. I didn’t want to make the grandfather sound like a horrible man. They are normal people who don’t wish evil. For Chuskit, I didn’t want a syrupy sweet girl like how the society usually perceives girls. She is gritty, and wouldn’t go down without putting up a fight. I wanted to gently say that these are real stories and let’s look at real stories than epitomise girls by making them devi or super heroes.

Recommended

This is a feminist film off screen, too. First of all, this is a film about a girl. She is the protagonist. Off screen, most of the heads of department who worked on the film are women. The girls had so much fun shooting the film. Everyone, including the grip boys to my assistants, partied every night. My mentor at NFDC was a woman. I had three women financially backing me – Wishberry’s Priyanka and Anshulika, and the largest investor, Namrata Goyal. Although I am good at working with both men and women, I particularly like working with the latter. I find it comfortable. It’s easy to relate to and work becomes much more collaborative.

How do you see this final phase of navigating film festival circuits? Is it the hardest part of your journey with the film?

Raising funds was tough, making the film was easy – especially because of the group of people I was working with. The movie-making part was joyful. When I began work on distribution and started applying to film festivals, I felt the heat. First of all, we don’t have a distribution system in place for indie films in the country. At some film festivals I went to, there were government officials representing the films from their country. When will that happen in India?

Navigating the film festival circuit has been tough. Since it’s my first feature film, I didn’t know how to go about it. I applied everywhere because I was certain of the idea that if you have made a good film, it can get into the Cannes. Now I understand that the parameter isn’t simply art. Many times, I was told that my film narrated a lovely, but simple story. Here, the girl doesn’t have an angst-ridden life. There are no great villains or complications in the story. Perhaps because of the same reason, the film always get slotted in children’s section. I believe it’s a film for mature adults too. Nevertheless, this has been an eye-opener for me. Next time when I am writing a script, I will position it accordingly.

Across the world, cultural funding is getting cut. As a documentary filmmaker, do you feel the ripples of it?

Absolutely yes. I do commissioned work. Earlier, we used to get a good six or seven months to work on a project – to script, do the recce, prepare, shoot and edit. It gradually got reduced to around four months because funds have started drying up. Old school documentaries are getting replaced with reality shows because they are easier to film and cost less. I would say, making a living out of documentary filmmaking has become increasingly difficult.

Is crowd funding an effective way out?

I am not an expert, but based on my personal experience, I found it difficult to do crowd-funding. Instead of that, we could follow the really old way of getting someone rich to commission the project. Everything is corporatized now. Then why not use it to create works without them calling the shots?

Pictures courtesy: Chuskit.com

*****