Gopi Sunder, the most sought-after composer in Mollywood at the moment – “almost all Vishu movies are mine,” he laughs – keeps a cool head more often than not. He’s not trained in music; doesn’t understand raagas or gamakkas, and believes there are certain advantages of not having learnt them. “I don’t have to unlearn the raagas to be creative. Cinema is not a place to display your erudition,” he says.

The accusations of plagiarism against him don’t bother him either.

Bizarrely, he doesn’t refute them.

Sometimes, the director would like a tune, and would want the composer to do something similar, Gopi explains; so he’d tweak notations enough to not get into legal trouble. “Of course, that doesn’t fool people, but I’m not ashamed to admit it in public. The critics and trolls cannot haul me to court over this.”

1

The notes come to Gopi anyway; formal training or no.

That too, at the opportune moment.

“I would be in a trance, then…”

Bhavas are his primary source of inspiration. When you arrange notes in a certain way, they emote, he declares. “Khamboji, Hamsadhwani, Mohanam… the names aren’t important to me. I look for the emotions that the notes convey.”

He often breaks into a song during our conversation. Or a random tune. One time, it’s Ethu Kari Raavilum, a popular number from the movie Bangalore Days – and his favourite. To Gopi, the impromptu songs and tunes are parts of natural speech. He uses them as one would an adjective. To describe or enhance something he says, to drive home a point – or to merely exist as a dramatized expression that just doesn’t seem out of place. Music seems to be an organic extension of his personality. He’s fluent in music-speak. So when Gopi says, “I don’t think there was a particular moment when I decided to make music my career; it’s always been a part of my life,” I’m quite inclined to believe him.

*****

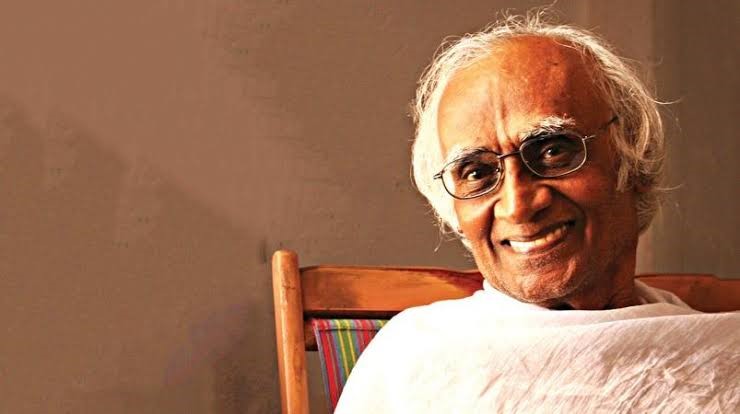

I reach Gopi Sunder’s studio in Kochi on a March afternoon, a week before the release of the now-popular soundtrack from the audio album of Amal Neerad’s CIA. A bunch of young programmers sit in the hallway, earphones plugged in, glued to their computers.

A few minutes later, the composer ushers me in.

I ask him about the projects he is working on.

A wide smile.

“Several,” he says, leaning back on the sofa. “Mexican Apaaratha, which released last week, Take Off, Amal Neerad’s Comrade In America, 1971: Beyond Border, Georgettan’s Pooram, Sathya…”

I am hardly surprised. If there’s something Gopi is known for other than his music-making prowess, it’s his fast-paced working style, coupled with a fine understanding of commercial cinema. “I have experience of over 20 years in the industry. That helps,” he says. “I work on a tight schedule. To me, the technical process of composing is easy. I’d be thinking about music all the time, and when I finally sit down to work, it gets done quickly.”

This working pattern, however, isn’t “mechanical”; Gopi just doesn’t let those “mood-swings” upset his work. A skill that comes from experience. He calls the process artistic, even spiritual. Sometimes draining, but mostly satisfying.

Usually, Gopi listens to a script outline or a situation-description and begins working on a tune right away. “I prefer to compose in the presence of the singer, lyricist, director, and scriptwriter. I don’t need solitude or privacy. Sometimes, I make a tune while hanging out with them in a tea shop. I sing in the public, though I am not a good singer.”

*****

Over the years, Gopi Sunder has created some of the most popular ‘mass’ numbers in Malayalam, the latest being the leitmotif of Puli Murukan. It seems effortless from the outside. “It’s in fact more difficult to compose a fast number in Malayalam,” Gopi laughs. “You should know the youth to make a popular song. To understand that, I go to theatres, tea shops…the places that people frequent. I interact with college students. I have never cut myself off from the public, but have become a part of it. It becomes easy to cater to their taste then.”

Of course, it’s not easy to make songs that stay with the audience for a long time. Especially now. “The world is busier,” agrees Gopi. “Now, by the time people grow fond of a song, another number would top the music charts.” Yet, the composer believes there’s space for all kinds of music. “I have noticed that the younger generation listens to both old and new songs. That’s an encouraging trend. I listen to songs by Baburaj and MS Vishwanathan as much as I enjoy the new soundtracks.”

Gopi is also an ardent fan of commercial cinema. “I watch a lot of films – commercial as well as classics, from all over the world. I would say that the composer who is used to working in commercial films, can work in art films with equal efficiency, but not vice versa. Not because composing for commercial films is more difficult, but because they look at commercial films as lowly.”

2

Gopi Sunder, as he has admitted in many a TV interview, owes a lot to his failure in his tenth standard board examinations. He discontinued his education after he failed the exams, and joined the team of composer Ouseppachan, his father’s friend. The journey since hasn’t been easy, he admits. “People look at me and say I’m lucky. But they don’t realise that this did not happen in a day. I toiled for 12 years to get my first film assignment. As a background music composer in Big B, and later, as an independent composer in Siby Malayil’s Flash.”

Gopi Sunder, as he has admitted in many a TV interview, owes a lot to his failure in his tenth standard board examinations. He discontinued his education after he failed the exams, and joined the team of composer Ouseppachan, his father’s friend. The journey since hasn’t been easy, he admits. “People look at me and say I’m lucky. But they don’t realise that this did not happen in a day. I toiled for 12 years to get my first film assignment. As a background music composer in Big B, and later, as an independent composer in Siby Malayil’s Flash.”

His highly successful oeuvre includes songs like Olanjali Kuruvi (from 1983), for which he roped in veteran singers Jayachandran and Vani Jayaram. The background score that he’d composed for 1983 fetched him a National Award in 2013. Most of his background scores, and leitmotif bear his signature, I tell him. While, according to many composers, an ideal score must blend into the narrative, Gopi says, “It depends on the nature of the film. Some require a score that blends with the narration, some need a track that stands out on its own. What makes a background score extraordinary is the sensibility with which it’s used in the film. It should convey the essence of a scene.”

One of his favourite background scores in Malayalam cinema is that one in Manichithrathazhu.

The electrifying, sometimes overbearing, background scores in Indian commercial films, are sometimes necessary, says Gopi. “In India, we have movies where the hero fights off 10 men single-handedly. For such highly-fantasised sequences, we need punchy music.”

Gopi Sunder’s work in films like Charlie, Ustad Hotel, and Kali have been much appreciated.

“I am ready to do all kinds of films. The directors I work with have varied sensibilities. Ultimately, my job is to keep my clients satisfied. That would give me more work.”

I remind him of a recently-released movie for which the background music that he composed had fallen flat. “I know it didn’t work,” Gopi admits. “Sometimes, I tell the directors how to use a score. I tell them where to add the BGM and where to use silence. But if he/she is so persistent that they need the film to be filled with music, I can’t help. I would try further only if the project is one I feel so emotionally attached to. Again, if it’s a film that makes you go ‘wow’, that would definitely be helmed by a director who is sensible enough to know that the film doesn’t need to be filled with sound tracks.”

He pauses, and then adds, “but if the director wants me to fill the film with loud music, and kill it, I would do that too. To survive in the industry, one has to be ready to face such clients.”

Needless to say, there’s no filter that Gopi applies to the projects that he sings. He takes up everything. He works with “all kinds of people” in “every kind of film”.

“I believe there’s an audience for every type of filmmaking. If you want to be in the industry, you cannot afford to be choosy.”

Earlier in his career, Gopi had worked on advertisements. He still does sometimes, between film assignments. Once in a while, he scores for short films too. “I can do any number of films simultaneously. Once, I’d worked on 28 films including some Telugu and Tamil films. I began doing Telugu because they make you feel very comfortable. They pump in good money because they trust my abilities. The songs I composed for the seven to eight Telugu films have done very well.”

Gopi wants to be remembered as the person who took a road less travelled. “Remember when the first posters of Big B appeared on the walls of Kochi? People said it looked like a jeans advertisement starring Mammootty. They hadn’t seen such a chic, modern movie in Malayalam before. Didn’t Big B change the face of Malayalam cinema? Similar difference has happened in music too. It’s more experimental.”

*****

gopi1

The composer thinks it’s a good time for budding singers who want to take up music as a career. “Earlier, there were just a few singers in the industry – Yesudas, Chithra, MG Sreekumar….Now there many of them, and they are all busy with shows and programmes in and outside the country.”

Gopi has a band, Band Big G, with which he does live shows in Dubai. “It’s part of the brand building process,” he says. He is the only permanent member of the band.

Recently, Gopi also launched his own music company. “I haven’t charted out a concrete plan for the company, but the goal is to handle the audio market deals and royalty business – YouTube, audio of the films I like, etc. – by myself. It’s like an investment.” He also looks at this company as something he can retire into. “See, this whole set up that is in existence now – director and producer approaching a music director to compose music – will change and a more a systematic corporate set up will come up soon.” For instance, he has programmers who work with him day and night to program the tunes that he composes. Gopi claims to be a programmer himself. If the project is something that he finds special, like Ustad Hotel and Take Off, or those that need really good attention, like Pulimurugan, he would sit down and work on everything from composing to programming, all by himself.

Ustad Hotel is, again, one of the few movies that Gopi Sunder is personally attached to. Another such movie is Bangalore Days. The Sufi-style music that he tried out for Ustad Hotel earned him a lot of praise.

The composer, however, says that the repeated use of Sufi elements in his songs is incidental. “I used it in Anwar and Ustad Hotel, which had an Islamic background. In Charlie, I used it in a scene where Dulquer’s character is walking out of a lodge with a child whom he rescued from a pimp. Martin said he was not sure about using a Sufi piece there since Charlie isn’t affiliated to any particular religion. But I knew this would touch a cord with Dulquer’s biggest fan base, the Malabar region, which otherwise, might not be fond of a film like Charlie. I understand how audience’s psychology works inside a theatre. In a scene as this, where Charlie acts like a demi-god, a savior, people would see only Dulquer. So it’s best to play to the gallery by cashing in on his off-screen image. The Sufi theme song worked out fantastically.”

3

He begins composing in silence. That’s Gopi’s first note.

There’s a method of composing that many use, Gopi explains, of adding a tune to a rhythm. He doesn’t do that.

“Once I hear a director’s narration, I sit down and hum a tune to him. If he likes it, I will begin orchestration. There is no technology dependence here. I am trying to use less and less of technology.”

Although Gopi is adept at using technology, he’s careful with it, so as to not lose the “soul” of his music. “I started off as a live music composer. Even now, I am confident that I can compose live with 100 pieces of orchestra in front of me. That’s something I learnt from Osephachan, whom I assisted for many years. I have 23 years of experience. I have done it all. I don’t think anybody else in my generation can claim this,” he says.

Earlier, there was an impressive way of composing, Gopi recalls. “Musicians and composers would meet at a place and start working on a song. I want to bring it back, systematically, with effective use of technology. I want to include singers in the process of composing. Those days, singers like Dasettan and Janakiyamma knew the pain that went into the process of composing. That made a difference in their singing too.”

*****

Gopi Sunder is someone who hardly loses his temper. “I live in the moment,” he says. The latest accusation of plagiarism levelled against him is that of copying the tune of “Njan Ninne Thedi Varum” – a song in the album of Jayaram’s Sathya – from the song “Halena Halena” in the Tamil film Irumurugan.

Recommended

He handles the merciless trolls on social media platforms effortlessly, giving it back in kind. When I ask him if filmmakers themselves tell him to plagiarise songs, he ignores the question with a smile. A sly response soon follows, “Do you think I’m so crazy or talent-less to plagiarise songs all the time?”

“This is how it happens,” he later adds, “the editor, while doing rough cuts, would lift a soundtrack of their choice to fill a portion. The director, after listening to it, might grow fond of it, and would ask the music director to do something similar. Most of the time, it’s hard to convince them with another tune. They will think the copied one is better than an original tune, even when that’s not the case. It’s human psychology.”

He laughs.

A recent status on his Facebook page conveys much the same:

gopi-status

[There is greater audience for ‘copied’ songs than original tunes.]

So, Gopi tweaks notations to satisfy the directors. Tweaks them enough to not land himself in legal trouble.

The Indian Copyright Law defines ‘musical work’ as “a work consisting of music and includes any graphical notation of such work but does not include any words or any action intended to be sung, spoken or performed with the music. A musical work need not be written down to enjoy copyright protection.”

“Of course, people will know,” Gopi agrees. “They will definitely spot similarities between two songs.”

To make up for all the songs that go wrong for reasons which are not in his control, Gopi Sunder churns out brilliant original scores time and again. “All the allegations and criticisms motivate me to make better songs,” he shrugs. “Instead of spending my time and energy in reacting to trolls and defending myself, I deliver a super-hit song immediately. Like Ethu Kari Raavilum, for instance.”

*****

The Gopi Sunder interview is a Silverscreen exclusive.