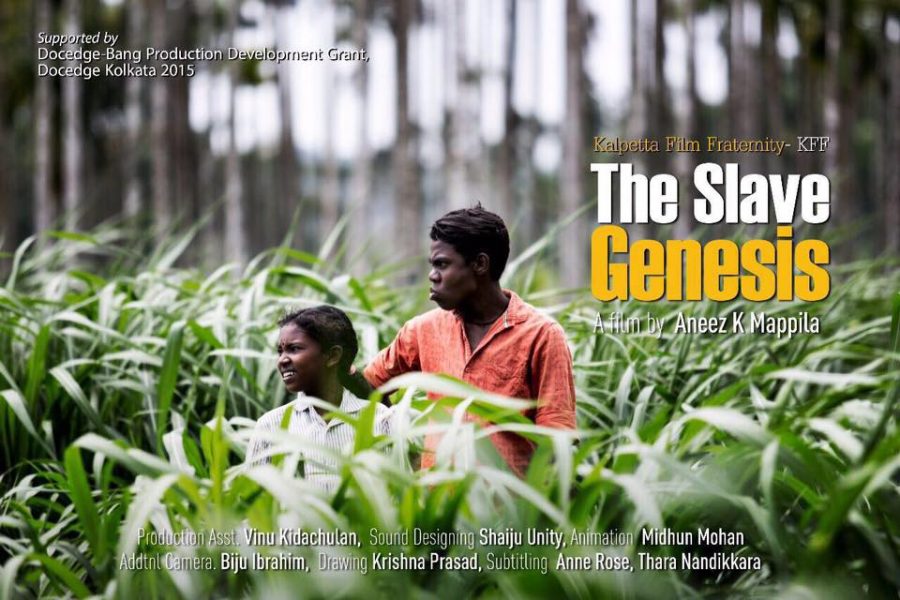

A sense of gloom pervades The Slave Genesis, a documentary film on Paniya, an aboriginal group in Kerala’s Wayanad district. Directed and shot by Aneez K Mappila, a young journalist from the district, the 60-minute long film takes you to a Paniya residential colony in Wayanad where the funeral ceremony of one of the workers who died of unnatural causes is underway. He was brought dead from a ginger estate in Coorg, where he worked as a manual labourer. The man was said to have consumed pesticide. His lifeless body, flanked by mourning family, inspires an old ritual singer to begin a Penappaattu, the ‘deadman’s song’ that talks about centuries of exploitation that his community had gone through.

The film starts off as an intimate work, partially inspired by Aneez’s memories of his childhood spent in his ancestral house in Kalpetta. “I had filmed several things, but when I witnessed the funeral ceremony and listened to Penapaattu, I realised this is what my documentary should be about,” says Aneez.

Penapaattu is a post-death ritual in the Paniya community. The singer is called ‘atholi’, and he represents the dead man’s soul. “Rarely do people from outside the Paniya community get the opportunity to witness and record the singing of Penappattu. It is a very private ceremony. I was lucky because over the course of shooting the documentary, the atholi and I had become friends,” says Aneez. The song is performed for 12 hours, from 5 am till 5 pm. The atholi neither takes food nor leaves his seat during this time.

“Animistic spirituality of the Paniyas is what I found the most striking,” says Aneez. “In Pennappaattu, the dead man speaks respectfully of the souls of all animals and birds. Their culture believes in humility. Penappaattu is a layered text which needs to be studied in detail. So far, no one has done it because the Paniya language has no script.”

Aneez’s film showcases the Paniyas’ spirituality through monologues. There is Noonji, a Paniya old man who earnestly narrates how his former master, a Muslim feudal lord, destroyed a sacred grove where a seven-headed serpent resided. “That day, my beloved master turned mentally deranged,” says the man, countering a popular rumor that the feudal lord turned insane after he found all his money and valuables stolen one day. In a later instance, a young man, the brother of the recently deceased, warns the filmmaker to never take the road that passes by the burial ground. “The spirit will take you for a ride. You will be lost. He will make you lose your way, like how you get confused and lose your way when you go to a city,” he says. Aneez cites these myths as an example of how different Paniyas are from the urbane Malayali community. “They have a unique culture. Their traditions and societal codes are different. The mainstream society has never tried to understand these people who are the largest tribal group in Kerala,” he says.

How such a community, which was leading a life intrinsically connected to nature, ended up as a clan of slaves is one of the pivotal points Aneez’s film focuses on. “To the people who migrated to Wayanad from other parts of the state for agriculture, the Paniya spirituality barely mattered. They destroyed the sacred groves Paniyas had been safeguarding and worshiping, and enslaved the Paniya men using alcohol,” says Aneez.

*****

The name Wayanad comes from two words – ‘Vayal’ and ‘Naadu’ which mean agricultural field and land respectively. The district has a huge population of aboriginal tribes, and among them, Paniya is the largest community. They are spread out all over Wayanad, living in tribal colonies and settlements.

Aneez completed the film over a period of three years. He travelled in and around Wayanad, meeting Paniyas at their residential colonies in Wayanad and coffee and ginger estates in Karnataka. His grandfather, one of the earliest Muslim agricultural migrants to Wayanad, and books such as “Keralathile Africa”, written by K Panoor, and the texts written by British museologist Edgar Thurston, were his primary sources of information.

One of the instances in the documentary shows an inebriated Paniya man whom Aneez met on the ginger fields of Coorg, singing a film song and dancing in a dim-lit labor camp. The man, inspite of his animated expressions, cuts a sombre figure. In the following sequence, one of the workers explains in a melancholic voice that the landowners provide them with rationed quantities of alcohol every evening, thus binding them to the habit forever. “Paniyas are widely used as cheap labour in Wayanad and Karnataka. There is hardly a single coffee, ginger and pepper estate in this region which doesn’t have Paniya workers,” says Aneez.

Recommended

“I had aspired to make a more detailed film, but couldn’t for many reasons,” says Aneez. “I could film just around 20 percent of what I had seen and experienced during the process of making the documentary. I had found myself in complicated situations where carrying a camera wasn’t an option at all, ” he says, citing an incident in Coorg’s ginger fields where he was denied access on the second day because they turned suspicious about his intentions.

After completing his diploma in journalism from Kozhikkode Press Club, Aneez started working as a documentary filmmaker. Three years ago, he made his first project, Vithappaadu, which is also set in Wayanad.

The Slave Genesis is co-produced by Singapore-based Bang Production Docedge, Kolkata and Kalpetta Film Society.

*****