Nineteenth-century poet, philosopher and Hindu-Muslim syncretic saint, Shishunala Sharif’s most famous poem starts with the words kodagana koli nungittha – the hen swallowed the monkey. The poem then talks of a goat that swallowed an elephant, the wall that swallowed the paint, and the chaff that swallowed the husk. The poem’s enduring quality is its absurdity, but also its open-ended-ness. What do these animals, plants, and objects stand for? Why are they all swallowing each other?

Perhaps the answer to this metaphorical riddle is in the poem’s most literal line, aadalu banda paataradavana maddali nungittha – the musician who came to perform was swallowed by the drum.

Is it the drum that makes the music? Or the musician?

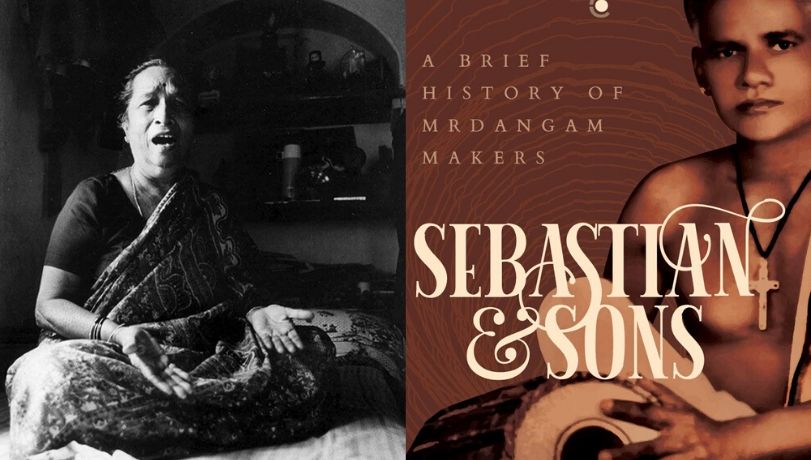

Musician-activist-writer TM Krishna’s quest for the answer to this question is his latest book Sebastian & Sons, (Context, 2019) while another book I discovered a couple of weeks ago, Deepa Ganesh’s biography of Gangubai Hangal, A Life in Three Octaves, (Three Essays, 2014) deals indirectly with the same question. While Krishna’s book deals with mridangam makers who are largely Dalit Christians, Ganesh’s book deals with Hangal, a vocalist from the traditional (and marginalised) musician community.

The two issues where the books intersect are – what is common to artistes and those who make the instruments of art? Why is it that we value one kind of performer over the other?

What drives artistes and mridangam makers?

Deepa Ganesh writes at length of Hangal’s abiding quest for perfect ‘sur’. As Ganesh puts it, “Music, for Gangubai, was an expression of faith and the note had to be searched and discovered each time a phrase was attempted.”

Hangal was a vocalist, and her instrument was her vocal cord. Training this instrument was a task in itself. Sometimes, her guru Sawai Gandharva gave her one phrase to practice for days together. He believed in teaching her only four ragas, after which she was on her own. She spent many years of her life rocking her children’s cradles while doing kharaj sadhana, or voice exercises in the lower octaves. But when it came to her daughter, her guru said she didn’t need to do kharaj sadhana because her voice was so sweet anyway. Different kinds of instruments need different kinds of maintenance. The stories of Hangal’s relentless practice and her battles with her voice show that training yourself to control the instrument within the body is no different from training yourself to control an external instrument. They both need care, they can both be petulant. And, to attain sur, you need to allow both to swallow you.

The sub-title of Krishna’s book is “A Brief History of Mrdangam Makers”, and in tracing this history and the people who make various parts of this instrument, from the carpenters and the abattoirs to the craftsmen, Sebastian & Sons in a sense makes an argument that the instrument does swallow the performer.

What the book subtly points out is that there are two performers – the mridangam player who plays on stage, and the maker whose creation is on stage. The lifelong obsession of both these performers is the urge to extract the best ‘nadam’ (the south Indian equivalent of ‘sur’) from the mridangam. Getting this elusive nadam, whether for Gangubai Hangal, a mridangam maker or a mridangam player is a function of both training and innovation; neither works without the other.

Krishna writes about Umayalpuram K. Sivaraman, saying, “… I challenged myself: is the nadam in my hands or in theirs [the makers]?” Later in the book, we hear of Sivaraman adopting innovations to the instrument to get that exhilarating nadam he is known for. Training your hands can only take you so far – you need innovation too. Conversely, Krishna writes about Palghat Mani Iyer’s fetish for a spectacular sound from the toppi (or base head) of his mridangam. Iyer’s rival, that incomparable genius Palani Subramania Pillai had the gift of that tone, and Iyer drove Parlandu, his mridangam maker mad with innovations to the toppi that would get him the same sound. Finally, Parlandu told him, that that sound is not in the toppi, but in Pillai’s hands.

Krishna shows us that even mridangam making needs innovation and training. Tying the pinnrasattai, or the coir that holds the head of the mridangam together, is a rhythmic process and in doing it well, like playing the instrument itself, the maker must train his body and commit the process to her muscle memory. As any instrumentalist will tell you, the day the instrument feels like an extension of your body, when you are able to express your mind on the instrument without any barrier, you are ‘ready’. Interestingly, at the book launch in Chennai, a mridangam maker from Andhra used the same word; he said that his son was now ‘taiyaar’ (ready) for mridangam making. It means that the implements, the raw materials and the processes are now extensions of his body.

Why are the makers sidelined?

People often speak about the antiquity of Carnatic music, of how it has been around for millennia, some tracing its roots to the sama veda. But in doing this, people tend to forget that Carnatic music is modern, contemporary and evolving all the time. Take any ‘modern’ musician – from Bombay Jayashree to Arun Prakash – and you can immediately tell that their music is ‘newer’ than their musical ancestors. Similarly, mridangam making has undergone innovations through the decades. In not recognising these innovations, or attributing them to mridangam artistes themselves, the Carnatic discourse has pushed the makers’ contribution to the sidelines.

Krishna places the blame at the feet of caste for this – most mridangam makers are Dalit Christians. Few others work with animal skin, for working with skin puts them in the ‘impure’ side of the caste equation. As Krishna says, just a few decades ago, they were not even allowed inside the homes of the mridangam artistes. Caste, thus, makes them invisible. Their names, their stories are largely unknown. We are quicker to recognise innovations to the music – a novel raga, a new rhythmic pattern – but we take longer to recognise the improving instrument because it happens beyond our eyes. Further, Krishna rightly argues, Brahmin musicians are seen as those who provide the makers with the knowledge, and the makers are seen as mere tools.

Even Gangubai Hangal suffered at the hands of caste. Her childhood in a Brahmin Agrahara where she faced overt and covert discrimination, writes Ganesh, had a profound impact on her. She remarked to her fellow women musicians from the devadasi community that when male musicians attain greatness, they are called ‘Ustad’ or ‘Pandit’, whereas the women from the performers’ community will always remain Gangubai, Kesarbai or Hirabai. Even her “penetrating search for the note”, as Ganesh puts it, did not put her on the same pedestal as her male counterparts.

In my opinion there is also another reason for this perceived hierarchy between ‘art’ and ‘craft’. The rhythms of a mridangam artiste are ‘art’ – they exist for their own sake. But the techniques of a mridangam maker are for the instrument that produces the ‘art’. In other words, the instrument is a means to the music. Further, a musician is looking for spontaneous self-expression, whereas the craftsman is bound by the need for consistency. Each mridangam must be of the same quality, must be as similar to the previous one as possible, leaving room, of course, for customisations for individual artistes. A spontaneous craftsman is a bad one.

In the documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi about legendary sushi chef Jiro Ono, there is a student of Jiro’s who’s spent years of his life in Jiro’s kitchen only learning how to make rice. Every step of the sushi making process from selecting the fish, to buying the rice from a man who will sell his rice to no one else, to cooking the rice, cutting the fish and finally making and serving the sushi itself is seen as a sacred ritual that needs years of training and repetition. Jiro does dream up new sushi, but for most of his life, he’s doing what he’s always done, honing his craft, training his hands, training his nose and his eyes in the search for perfection. Japanese culture reveres Jiro for what he does, for his labour, for his exacting standards, for his single-mindedness. Still would we consider Jiro an artist? Does he create beautiful one-of-a-kind art objects?

One way to think about this distinction is to put art and craft on a spectrum – all musicians need to be craftsmen, for they need technique and they need repetitive practice. Similarly, all instrument makers need to be artistes, for without artistry, they cannot be master craftsmen. But they are two persons who perform distinct jobs – neither can become the other. Seen from this lens, there is no hierarchy between art and craft; they are two different but allied spheres of human achievement.

Recommended

The reason for the perceived hierarchy between art and craft, can be attributed to caste, but not entirely. This hierarchy exists even in societies that do not have caste. Beethoven is always more revered than Stradivarius. Even within the upper-caste Carnatic mridangam world, Krishna writes about the case of Vellore Ramabhadran, a Brahmin and one of the most famous mridangam artistes of all time. Ramabhadran’s nadam was second to none. It was sweet and pure. His rhythms were uncomplicated, but no one could deny that they had something special. His understanding of the pulse of the concert and his ability to raise its level were acknowledged by every artiste he performed with. But he did not indulge in complex mathematical patterns, his playing hid no great mysteries. In other words, he was more on the craftsman side of the spectrum. And he was derided for this, even though other mridangists could never bring his consummate skill-set to the table.

When we recognise that art and craft are two different skills, the question of placing them in some hierarchy disappears. As Sharif said two hundred years ago, when a great performer performs, she is consumed by her instrument. Whether she is performing art or craft or something in between, no one can take that away from her.